OCT在缺血性视神经病变中的应用

介绍

缺血性视神经病变是最常见的非青光眼视神经病变之一,尤其在50岁以上的患者中,是该年龄组最常见的导致急性视力丧失的视神经问题,估计每年发病率为2.3-10.2/100,000[1-5]。视神经缺血可由多种原因引起,其中最常见的NAION的确切病因尚不清楚。血管病变,如巨细胞动脉炎,可导致视神经缺血,而急性出血、术中血液流动和血液稀释、休克,均可引起视神经乳头或球后严重的低灌注而损伤视神经[5]。OCT和OCTA已经被试用于描述疾病的严重程度,以及识别可能导致疾病发病和进展的潜在血管异常。尽管迄今为止的研究尚未让我们开发出新的治疗办法,但是我们正在进行努力的目标之一。

NAION

NAION患者通常主诉无痛性视力丧失突然发作。视力下降和(或)视野丧失以及受累侧瞳孔传入缺陷(如果单侧且对侧眼正常)是该病的标志性体征,急性期的检查也显示视盘水肿,我们认为这是由于供应视神经前部的小血管灌注不足造成的缺血所致[1,4]。如果对侧眼从未发生过类似的事件,它通常呈现出一个小的、拥挤的结构——被称为“风险之盘”,杯盘比例很小。

急性视盘肿胀可在症状出现后的前2-3周进展,6周后开始缓解。最终,视盘变成扇形(图1)或全盘性苍白[1]。在NAION患者中,视神经的磁共振成像通常是正常的,因此没有临床指征,尽管在某病例中诊断不确定,但磁共振成像轨道与造影剂可用于排除NAION的压缩或炎症病变[5]。

OCT:测量视网膜乳头周围神经纤维层厚度的价值

OCT已作为一种客观的视神经病变诊断、监测,及与其他视神经病变鉴别的技术。最初用OCT来测量乳头周围视神经纤维层厚度。在NAION早期,视神经纤维层OCT可能显示相对于对侧眼的增厚[6-8]。视神经纤维层增厚程度在亚急性期和前部缺血性视神经病变发生后6个月迅速下降。随访时间较长的研究显示,在第6个月和第12个月之间,视神经纤维层厚度没有显著下降[9]。视神经纤维层变薄的严重程度与视野缺损和视力损失的程度相关;在具有典型下部视野丢失的NAION的眼睛中,相对于未受影响的视网膜下段和对照眼,视网膜乳头周围相应的上象限和扇区的视神经纤维层厚度显著降低[10]。研究还表明,平均视神经纤维层厚度每减少一微米,视野平均偏差就会减少2分贝。此外,视力是每减少1斯内伦线伴随着1.6μm的视神经纤维层损失[7]。在动物(大鼠)NAION模型中,OCT测量视神经纤维层厚度的有效性与组织学测量具有可比性,因为OCT测量的视乳头周围视网膜内厚度与组织学制备测量的厚度是相关的[11]。因此,视神经纤维层OCT可以帮助识别视盘急性水肿,特别是当病变轻微时,并用于评估NAION中视神经纤维层随着时间的损失。随着病情的发展和消退,跟踪视神经纤维层的厚度可以帮助临床医生确保患者遵循着正常或预期的病程,因为当出现苍白时,眼底肿胀的消退可能更加难以识别。视神经纤维层OCT也可以检测对侧眼的亚临床水肿,这可能表明即将发生NAION,并提醒眼科医生在不久的将来可能会出现视力丧失。

利用OCT测量黄斑结构变化的价值

视神经病变的视神经纤维层厚度测量作为视神经完整性的结构测试确实存在一些局限性。并不是所有的研究都发现视神经纤维层扇区变薄或变化与典型的下部视野缺陷之间存在很强的相关性[10]。其他出版物报道了视野和单个视盘扇区之间的有限相关性[12],一个重要的考虑是乳头周围视神经纤维层结构与视野检测显示的视网膜位图并不精确对应,即乳头周围视神经纤维层图以视盘为中心,距中央凹鼻腔15°(此处视野位于中心)[13]。此外,视网膜神经纤维层由视网膜神经节细胞轴突组成,考虑到在NAION的中央视力缺失通常与乳头黄斑束的更大损伤有关[14],评估神经节细胞加内丛状层和黄斑参数可能是一种比乳头周围视神经纤维层[15]更有用的测量早期视神经损伤的方法。其实,黄斑的厚度和扇形体积在显示出比视神经纤维层参数与视野敏感性变化更强的相关性上都有优势[12]。此外,NAION后,鼻内和外黄斑区变薄与最佳矫正视力显著相关[16],而NAION后视力丧失的程度与乳头黄斑束损伤的严重程度直接相关[14]。

随着光谱域OCT和黄斑分割算法的技术及分辨率提高,测量包含神经节细胞体、它们的轴突和树突在内的单个视网膜层,特别是神经节细胞、黄斑视神经纤维层和内部网状层成为可能。Rebolleda等人[14]证实至少6个月前经历过NAION的患者神经节细胞层变薄。他们发现视力和神经节细胞加内丛状层之间存在显著的相关性,其中内部网状层的中央部分相关性最强。Larrea等人[17]假设神经节细胞丢失可以用于检测NAION急性期的早期轴突损伤,而这是通过测量视神经纤维层无法检测到的。之前的研究者们[18]在基线和NAION后1、3和6个月进行了乳头周围视神经纤维层厚度、黄斑总厚度和神经节细胞加内丛状层厚度的纵向测量,并将结果与未受影响的对侧眼进行了比较。结果发现,在NAION急性期,患眼和未患眼的黄斑内环总厚度和全区域神经节细胞加内丛状层厚度没有差异,然而,由于乳头周围视神经纤维层水肿并延伸至黄斑外区,受影响的NAION眼的平均视神经纤维层厚度和外围黄斑总厚度显著增大。1个月时,NAION眼的神经节细胞加内丛状层明显变薄,3个月时继续变薄,6个月后趋于稳定。乳头周围视神经纤维层与内环和外环黄斑总厚度的变薄在3个月时首次明显。因此,连续的神经节细胞加内丛状层变薄发生在NAION发病后1-3个月,这与早期视网膜神经节细胞丢失的组织学测量相一致。Fard等人[19]揭示,缺血性视盘病变8天后开始,Brn3a染色的视网膜神经节细胞减少42%,此后持续2周。值得注意的是,黄斑总厚度和乳头周围视神经纤维层厚度显示了神经节细胞加内丛状层变薄后发生的延迟变薄。这种时间差可以解释为轴突早期肿胀及其混淆作用,或轴突前神经节细胞体早期神经退行性改变[20]。Kupersmith和他的同事[21]揭示,在NAION的亚急性期,显著的神经节细胞加内丛状层变薄(与正常眼相比<5百分位)伴随着视神经纤维层的持续肿胀,这表明视神经纤维层测量不能准确反映神经元复合体的损失。相应地,神经节细胞加内丛状层变薄的程度与1-6个月的视力和视野平均偏差减少直接相关[21]。

通过视神经乳头的结构分析探讨其发病机制

OCT与增强深度成像的进步允许了高分辨率的视神经深部可视化,包括筛板、布鲁赫膜孔,以及层前组织和层间深度[19]。我们之前的观察显示,青光眼患者的视神经乳头以筛板变薄为特征,与NAION眼的情况相反[22]。另一项研究报告了急性水肿的NAION眼与未受影响的眼相比,其层前组织增厚和布鲁赫膜孔增大,随着时间的推移,这些变化实际上逆转了[23]。增强深度成像OCT还显示了NAION中详细的视神经乳头拥挤,认为这是发生NAION的主要危险因素。OCT也改变了我们对巩膜管大小在NAION发展中可能作用的理解。共聚焦扫描激光检眼镜(海德堡视网膜断层成像II,海德堡工程公司,多森海姆,德国)的研究认为,与对照组相比,NAION眼的视盘直径和面积更小[8]。随后,Hayreh等人[24]假设“风险之盘”NAION患者的布鲁赫膜孔小于对照组一般人群,导致特征性视盘拥挤。然而,直接比较临床视盘/眼底检查和视神经乳头SD-OCT成像是不合适的,因为每一种方法获得的信息不同,没有可比性[25]。我们用增强深度成像OCT测量急性后NAION及其对侧眼的布鲁赫膜孔面积,并与正常眼进行比较。值得注意的是,三组布鲁赫膜孔面积相似[26]。类似地,一些时域OCT研究也显示,NAION患者的布鲁赫膜孔并不比年龄相似的对照组小[6,27]。另一项增强深度成像OCT研究也确定了NAION和对照组的布鲁赫膜孔区域没有显著差异[28]。我们还测量了急性后NAION眼的层前组织(内界膜表面与层前表面的垂直距离)。我们发现,与正常对照组的眼睛相比,NAION患者的眼睛和未受影响的对侧眼都出现了层前组织增厚。鉴于我们在患和未患NAION患者的眼睛中都发现了增厚的层前结构(图2),但我们认为这种变化并不是疾病的后果,而可能是导致疾病的[26]。另一项研究也发现,与对照组相比,NAION对侧眼的前层组织更厚,但不显著。更重要的是,增强深度成像OCT使我们能够测量乳头周围脉络膜厚度。我们小组发现,与对照组相比,受影响和未受影响的对侧眼NAION患者的眼乳头周围脉络膜结构比对照组更厚[30]。Pérez-Sarriegui等[31]和Nagia等[28]的研究证实了我们在NAION患者中发现双侧脉络膜增厚的结果。明显较厚的层前神经组织被增厚的乳头周围脉络膜推向前方,这两种特征都有助于NAION中出现“拥挤”的圆盘。

Spectralis OCT青光眼模块Premium(GMP)版提供了另一种使用布鲁赫膜孔作为边缘解剖边界的视神经乳头的分析方法[33,33],称为布鲁赫膜孔最低轮辋宽度。这个参数可能比乳头周围视神经纤维层厚度更准确地反映了视神经乳头开口的轴突,因为它垂直于神经组织轴线[33]。与未受影响的同眼和对照眼相比,NAION眼的布鲁赫膜孔最低轮辋宽度测量值变薄。值得注意的是,对侧未受影响的NAION眼,布鲁赫膜孔最低轮辋宽度明显较对照组厚,再次反映了NAION对侧眼的层前组织增厚[29]。此外,布鲁赫膜孔最低轮辋宽度有助于区分慢性NAION和青光眼。虽然青光眼和NAION患者乳头周围视神经纤维层厚度值的降低相似,但与NAION眼相比,只有青光眼患者的布鲁赫膜孔最低轮辋宽度值明显变小[34]。

NAION中的OCT血管成像:我们能学到什么?

虽然已有许多研究工具用于测量急性和晚期NAION的视神经乳头灌注[35,36],OCT血管成像的出现使我们能够定量评估不同疾病乳头周围和视网膜血管的循环,如青光眼、糖尿病、急性眼压升高和甲状腺眼病[37-40]。由OCT血管成像测量的视乳头周围血管密度除了能够分析总的视网膜乳头周边血管密度和脉络膜微血管,还能分析位于内界膜和视神经纤维层后边界之间的血管。

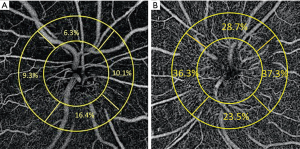

一些研究报道了在急性期和急性后期进行NAION后,视乳头周围OCT血管成像的发现。急性NAION的放射状周围毛细血管密度降低,且3个月内血管逐渐缩小,这与神经节细胞加内丛状层变薄有关[41,42]。Wright Mayes等人[43]也发现80%眼的视神经纤维层的结构性OCT损耗对应于放射状周围毛细血管的血流损伤。在视盘肿胀的眼睛中采用定制图像分析,去除主要血管,测量乳头周围毛细血管密度。与视神经乳头水肿相比,我们发现由于NAION导致的视盘肿胀的眼睛乳头周围毛细血管密度较低(图3)[44]。

尽管有多项研究已经报道[45-48],但OCT血管成像并不直接显示急性NAION视神经缺血。首先,我们认为NAION是视神经乳头板后节段急性梗死的结果,该节段主要由睫状体后短动脉供血[49]。利用现有技术,OCT血管成像显然无法显示这些深层血管。然而,更重要的是,在符合视野缺损位置的急性期NAION中研究者们发现了乳头周围血管密度的下降,与乳头周围视神经纤维层变薄的严重程度相关。这种变化模式与之前青光眼患者视野丢失的结果进一步吻合[45,50,51]。这一事实表明,放射状周围毛细血管的下降并不是青光眼视神经病变或NAION所特有的,它可能继发于乳头周围视神经纤维层丢失。在另一项研究中,我们比较了青光眼和NAION眼的乳头周围放射状毛细血管的密度,发现这两种情况下放射状周围毛细血管损失的程度没有区别[52]。值得注意的是,我们使用了视神经纤维层厚度匹配的中度或重度青光眼,因为研究表明,在青光眼中,视神经盘旁毛细血管密度损失越大,视神经纤维层损失也越大[51]。我们的结论是放射状周围毛细血管密度的损失似乎对这两种疾病(青光眼或NAION)都没有特异性,而可能是视神经纤维层损害的结果[45,52]。根据平均视神经纤维层厚度调整视神经损伤的严重程度后,视神经炎和NAION眼之间的血管密度出现了相似的衰减[53]。

很少有研究报道NAION中黄斑血管OCTA的表现。视网膜层自动分割到浅、深毛细血管丛[54]。OCT血管成像在急性NAION后,黄斑浅表和深层毛细血管丛显示出主要位于大血管附近毛细血管网的整体稀疏[48],而早期研究显示黄斑血管没有变化[55]。然而,在这些研究中,深毛细血管丛的分割容易出现投影伪影,即黄斑深部图像中浅表血管的重现。在另一项研究中,我们在解决了伪影问题之后,成像了青光眼和NAION急性期后的黄斑血管。虽然我们发现与对照组相比,NAION眼的黄斑下部浅表血管更少,但深层血管没有受到影响。因此,在某种程度上,类似于我们对乳头周围区域放射状周围毛细血管丢失的观察,在NAION中黄斑浅血管的丢失可能继发于神经节细胞复合体丢失,而不一定是病因或原发的。根据这个假设,我们注意到浅表血管密度与相应的神经节细胞复合体完整性和视野平均偏差之间有很强的相关性[56],而中央凹旁神经节细胞与黄斑深部血管密度没有这种相关性。用黄斑OCTA检测急性NAION有不同的结果,我们在急性NAION中的发现与后急性NAION的继发性微血管改变理论相反。在早期急性NAION中,尽管黄斑和近黄斑区的神经节细胞复合体没有受到影响,黄斑血管密度值与对照组相比还是显著降低[57]。这差异可能与NAION所处的阶段有关,有待进一步研究。

动脉前缺血性视神经病变

虽然巨细胞动脉炎是动脉前部缺血性视神经病变最常见的原因,但其他血管炎也可能导致缺血性视神经病变[5,58]。动脉前缺血性视神经病变患者的视力损失往往比NAION患者更严重[5]。巨细胞动脉炎时受累的视神经肿胀呈苍白色,动脉前部缺血性视神经病变中可不伴有视盘风险。Danesh-Meyer等人使用海德堡视网膜断层摄影术比较了NAION和动脉前部缺血性视神经病变后的视盘结构,发现在动脉前部缺血性视神经病变事件后有显著的视盘凹陷,而在NAION事件后没有发现[59]。相关视网膜或脉络膜缺血的发现高度提示巨细胞动脉炎[5]。与NAION不同,OCT尚未广泛应用于动脉前部缺血性视神经病变的急性期或慢性期。在最近的一项研究中,采用动脉前部缺血性视神经病变和NAION患者的视神经乳头及黄斑OCT测量脉络膜血管指数。动脉前部缺血性视神经病变患者,黄斑脉络膜血管指数明显低于非前部缺血性视神经病变患者,黄斑脉络膜血管指数与对照组无明显差异。此外,动脉前部缺血性视神经病变患者的乳头周围脉膜血管指数明显低于非前部缺血性视神经病变患者[60]。动脉前部缺血性视神经病变患者脉络膜血管指数的下降可能反映了继发于睫状后动脉血管炎低灌注的脉络膜变化[60]。与NAION相似,通过OCTA[61,62]也证实了动脉前部缺血性视神经病变中放射状周围毛细血管的缺陷,OCTA研究显示动脉前部缺血性视神经病变中对应于视野损失的视网膜毛细血管的灌注缺陷。然而,OCTA层状分析并没有突出荧光血管造影中看到的脉络膜/脉络膜毛细血管灌注缺陷,这表明荧光血管造影在检测脉络膜灌注缺陷时更加敏感,而OCT血管扫描可能会忽略脉络膜灌注中细微但可能具有视觉意义的缺陷[62]。

结论

OCT和OCTA可以更好地了解缺血性视神经病变的结构变化,特别是疾病消退时视盘、乳头周围和黄斑结构变化的演变。有了这些先进的成像方法,我们已经认识到一些比以前认知要多的方面,像NAION这样的疾病可能有不同的危险因素,进一步研究观察到的结构变化对该病发病的作用可能会利于我们发现更好的治疗干预方法。

Conclusions

OCT and OCT-A have allowed for a greater understanding of the structural changes that occur in ischemic optic neuropathies, and in particular, the evolution of changes in optic disc, peripapillary, and macular structures as disease resolution occurs. With these advanced imaging methods, we have recognized that there may be different risk factors for disorders such as NAION than previously thought, and further research into the contribution of observed structural changes to the onset of this disease may lead to better therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Fiona Costello and Steffen Hamann) for the series “The Use of OCT as a Biomarker in Neuro-ophthalmology” published in Annals of Eye Science. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aes.2019.12.05). The series “The Use of OCT as a Biomarker in Neuro-ophthalmology” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. PSS reports grants and personal fees from Quark Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hayreh SS. Ischemic optic neuropathies - where are we now? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013;251:1873-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hattenhauer MG, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, et al. Incidence of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;123:103-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Preechawat P, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, et al. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in patients younger than 50 years. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:953-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- . Characteristics of patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy eligible for the Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114:1366-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biousse V, Newman NJ. Ischemic Optic Neuropathies. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2428-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Contreras I, Rebolleda G, Noval S, et al. Optic disc evaluation by optical coherence tomography in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:4087-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Contreras I, Noval S, Rebolleda G, et al. Follow-up of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy with optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2007;114:2338-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saito H, Tomidokoro A, Tomita G, et al. Optic disc and peripapillary morphology in unilateral nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and age- and refraction-matched normals. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1585-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dotan G, Goldstein M, Kesler A, et al. Long-term retinal nerve fiber layer changes following nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Clin Ophthalmol 2013;7:735-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deleón-Ortega J, Carroll KE, Arthur SN, et al. Correlations between retinal nerve fiber layer and visual field in eyes with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:288-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maekubo T, Chuman H, Kodama Y, et al. Evaluation of inner retinal thickness around the optic disc using optical coherence tomography of a rodent model of nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2013;57:327-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papchenko T, Grainger BT, Savino PJ, et al. Macular thickness predictive of visual field sensitivity in ischaemic optic neuropathy. Acta Ophthalmol 2012;90:e463-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aghsaei Fard M, Fakhree S, Ameri A. Posterior Pole Retinal Thickness for Detection of Structural Damage in Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy. Neuroophthalmology 2013;37:183-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebolleda G, Sanchez-Sanchez C, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, et al. Papillomacular bundle and inner retinal thicknesses correlate with visual acuity in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:682-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kardon RH. Role of the macular optical coherence tomography scan in neuro-ophthalmology. J Neuroophthalmol 2011;31:353-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Buenaga R, Rebolleda G, Muñoz-Negrete FJ, et al. Macular thickness. Ophthalmology 2009;116:1587.e1-3. [PubMed]

- Larrea BA, Iztueta MG, Indart LM, et al. Early axonal damage detection by ganglion cell complex analysis with optical coherence tomography in nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014;252:1839-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akbari M, Abdi P, Fard MA, et al. Retinal Ganglion Cell Loss Precedes Retinal Nerve Fiber Thinning in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2016;36:141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Ebrahimi KB, Miller NR. RhoA activity and post-ischemic inflammation in an experimental model of adult rodent anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Brain Res 2013;1534:76-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chauhan BC, Stevens KT, Levesque JM, et al. Longitudinal in vivo imaging of retinal ganglion cells and retinal thickness changes following optic nerve injury in mice. PloS One 2012;7:e40352 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kupersmith MJ, Garvin MK, Wang JK, et al. Retinal ganglion cell layer thinning within one month of presentation for optic neuritis. Mult Scler 2016;22:641-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Afzali M, Abdi P, et al. Optic Nerve Head Morphology in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Compared to Open-Angle Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:4632-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebolleda G, García-Montesinos J, De Dompablo E, et al. Bruch's membrane opening changes and lamina cribrosa displacement in non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101:143-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: refractive error and its relationship to cup/disc ratio. Ophthalmology 2008;115:2275-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chauhan BC, Burgoyne CF. From clinical examination of the optic disc to clinical assessment of the optic nerve head: a paradigm change. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:218-227.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moghimi S, Afzali M, Akbari M, et al. Crowded optic nerve head evaluation with optical coherence tomography in anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Eye (Lond) 2017;31:1191-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan CK, Cheng AC, Leung CK, et al. Quantitative assessment of optic nerve head morphology and retinal nerve fibre layer in non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy with optical coherence tomography and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoloscopy. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:731-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagia L, Huisingh C, Johnstone J, et al. Peripapillary pachychoroid in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:4679-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebolleda G, Pérez-Sarriegui A, Díez-Álvarez L, et al. Lamina cribrosa position and Bruch’s membrane opening differences between anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and open-angle glaucoma. Eur J Ophthalmol 2019;29:202-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Abdi P, Kasaei A, et al. Peripapillary choroidal thickness in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:3027-33. [PubMed]

- Pérez-Sarriegui A, Muñoz-Negrete FJ, Noval S, et al. Automated Evaluation of Choroidal Thickness and Minimum Rim Width Thickness in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2018;38:7-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chauhan BC, Danthurebandara VM, Sharpe GP, et al. Bruch's membrane opening minimum rim width and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in a normal white population: a multicenter study. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1786-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reis AS, O'Leary N, Yang H, et al. Influence of clinically invisible, but optical coherence tomography detected, optic disc margin anatomy on neuroretinal rim evaluation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:1852-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Resch H, Mitsch C, Pereira I, et al. Optic nerve head morphology in primary open‐angle glaucoma and nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy measured with spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Acta ophthalmol 2018;96:e1018-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Traversi C, Bianciardi G, Tasciotti A, et al. Fractal analysis of fluoroangiographic patterns in anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy and optic neuritis: a pilot study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;36:323-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collignon-Robe NJ, Feke GT, Rizzo JF III. Optic nerve head circulation in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and optic neuritis. Ophthalmology 2004;111:1663-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jia Y, Wei E, Wang X, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of optic disc perfusion in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1322-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin YI, Nam KY, Lee SE, et al. Peripapillary microvasculature in patients with diabetes mellitus: An optical coherence tomography angiography study. Sci Rep 2019;9:15814. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moghimi S. Changes in Optic Nerve Head Vessel Density After Acute Primary Angle Closure Episode. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019;60:552-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jamshidian Tehrani M, Mahdizad Z, et al. Early macular and peripapillary vasculature dropout in active thyroid eye disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2019;257:2533-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma S, Ang M, Najjar RP, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in acute non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101:1045-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebolleda G, Diez-Alvarez L, Garcia Marin Y, et al. Reduction of Peripapillary Vessel Density by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography from the Acute to the Atrophic Stage in Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy. Ophthalmologica 2018;240:191-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright Mayes E, Cole ED, Dang S, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2017;37:358-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Jalili J, Sahraiyan A, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in optic disc swelling. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;191:116-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hata M, Oishi A, Muraoka Y, et al. Structural and Functional Analyses in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. J Neuroophthalmol 2017;37:140-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song Y, Min JY, Mao L, et al. Microvasculature dropout detected by the optical coherence tomography angiography in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Lasers Surg Med 2018;50:194-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu CH, Kao LY, Sun MH, et al. Retinal vessel density in optical coherence tomography angiography in optic atrophy after nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. J Ophthalmol 2017;2017:9632647 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Augstburger E, Zeboulon P, Keilani C, et al. Retinal and Choroidal Microvasculature in Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: An Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018;59:870-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olver JM, Spalton DJ, McCartney AC. Microvascular study of the retrolaminar optic nerve in man: the possible significance in anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Eye (Lond) 1990;4:7-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghahari E, Bowd C, Zangwill LM, et al. Association of Macular and Circumpapillary Microvasculature with Visual Field Sensitivity in Advanced Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;204:51-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yarmohammadi A, Zangwill LM, Diniz-Filho A, et al. Relationship between Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Vessel Density and Severity of Visual Field Loss in Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2016;123:2498-508. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Suwan Y, Moghimi S, et al. Pattern of peripapillary capillary density loss in ischemic optic neuropathy compared to that in primary open-angle glaucoma. PloS One 2018;13:e0189237 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Yadegari S, Ghahvechian H, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of a pale optic disc in demyelinating optic neuritis and ischemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2019;39:339-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campbell JP, Zhang M, Hwang TS, et al. Detailed Vascular Anatomy of the Human Retina by Projection-Resolved Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Sci Rep 2017;7:42201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu CH, Wu WC, Sun MH, et al. Comparison of the Retinal Microvascular Density Between Open Angle Glaucoma and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017;58:3350-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Fakhraee G, Ghahvechian H, et al. Macular Vascularity in Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Compared to Glaucoma by Projection-Resolved Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Am J Ophthalmol 2020; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Ghahvechian H, Sahrayan A, et al. Early Macular Vessel Density Loss in Acute Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Compared to Papilledema: Implications for Pathogenesis. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2018;7:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fard MA, Nozarian Z, Veisi A. Arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy with unusual systemic manifestations. Neuroophthalmology 2019; [Crossref]

- Danesh-Meyer H, Savino PJ, Spaeth GL, et al. Comparison of arteritis and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathies with the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph. Ophthalmology 2005;112:1104-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini M, Giannaccare G, Bernabei F, et al. Choroidal Vascular Changes in Arteritic and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;205:43-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balducci N, Morara M, Veronese C, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in acute arteritic and non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2017;255:2255-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaier ED, Gilbert AL, Cestari DM, et al. Optical coherence tomographic angiography identifies peripapillary microvascular dilation and focal non-perfusion in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102:1141-6. [PubMed]

马珂珂

西安市人民医院(西安市第四医院) 眼科住院医。2020年毕业于厦门大学眼科学硕士,工作一年已轮转过眼屈光科、眼表疾病科、中西医结合眼病科、糖尿病视网膜疾病中心,仍处于轮转工作阶段。由于研究生方向为眼表,故更擅长眼表相关的词汇和翻译,其他方向亦可。(更新时间:2021/9/9)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Fard MA, Ghahvehchian H, Subramanian PS. Optical coherence tomography in ischemic optic neuropathy. Ann Eye Sci 2020;5:6.