重症肌无力

重症肌无力(MG)是一种以自身抗体沉积于神经肌肉接头并导致眼外肌和骨骼肌无力为特征的自身免疫性疾病。重症肌无力的分类主要有以下几种方法:根据受累组织分布分为眼肌型和全身型、根据自身抗体的类型分类、依据发病年龄分类,以及依据是否合并胸腺异常进行分类[1]。在绝大多数MG患者的神经-肌接头中有免疫球蛋白IgG1和IgG3 抗体的沉积[2]。这两种免疫球蛋白在突触后膜与乙酰胆碱受体(AchR)结合并导致补体介导的损伤[3]。85%的全身型MG患者体内具有针对AchR的抗体,但这些抗体仅在50%的单纯OMG患者中发现[2]。在没有AchR抗体的MG患者中,可能存在抗肌肉特异性激酶(MuSK)抗体,抗低密度脂蛋白受体相关蛋白 4(LRP4)和集聚蛋白抗体[4]。在同一患者中,AchR抗体和MuSK抗体不会同时出现,但在某些情况下,LRP4和集聚蛋白抗体可与AchR抗体和MuSK抗体在一个患者中同时出现[5]。MuSK抗体相关的MG多发生于年龄较小的女性患者中,占血清阴性病例(未检测到AchR抗体) 的70%[6,7]。

一般来讲,MG的年发病率为0.04-5/100,000,年患病率为 0.5 -12.5/100,000[8]。该病在患病年龄、性别、种族没有差异,其中,OMG好发于男性。流行病学资料显示MG患者一代以内近亲属或兄弟姐妹中发展成为MG约为4.5%,提示该病具有较强的遗传特性[9,10]。MG的人群发病率和患病率都在增加,尤其是在老年人中[11,12]。小儿MG也可能表现为各种类型的眼球运动异常或上睑下垂。与成人一样,应对该疾病进行早期诊断以减少像延髓和呼吸肌无力等可能危及生命的MG相关并发症发生[3,13]。

临床表现

80%以上的MG患者主要表现为眼部症状(上睑下垂和(或)复视),尽管其他肌肉受累会导致吞咽困难、发音困难、咀嚼食物困难、声音改变、四肢无力,以及呼吸困难[14]。MG的标志特点之一是症状的周期性复发、缓解和MG危象[1],包括肌肉易疲劳和波动性无力[15]。肌肉无力症状会随着肌肉的重复使用而加剧,而休息和低温可改善症状。呼吸困难与吞咽困难出现在重症MG患者中,产生肌无力危象。MG的严重程度因人而异,各不相同,甚至在同一个患者不同时期也有不同[14]。OMG患者通常在疾病的前2年进展为全身型MG;泼尼松龙可能有助于延迟或防止全身型MG的发生,还可控制眼部症状[16,17]。合并其他自身免疫性疾病,如格雷夫斯病、抗体阳性甲状腺疾病和胸腺增生也可能增加前6个月内OMG进展为全身型MG的风险[18]。在具有MuSK抗体的OMG患者中,慢性眼肌麻痹很常见,共轭注视限制与低视力残疾有关[19]。

OMG的症状包括了因眼外肌波动性无力导致的上睑下垂、复视和聚焦障碍中的一种或多种[14]。MG患者的瞳孔反射,感觉功能和视力均是正常的[20]。上睑下垂可以是单侧或双侧的,并且可能会因为眼肌疲劳导致持续性向上注视[14]。OMG可以伪装成为任何无痛的伴有或不伴有上睑下垂的眼肌麻痹[21]。复视是一种常见症状,原因是眼外肌肌力减弱导致眼位错位。眼球先向下方注视,然后迅速向正前方注视,此时出现上睑一过性向上方收缩,这一现象被称为“Cogan’s眼睑颤动征”,可见于OMG[22]。超量扫视、生涩的眼球运动、眼跳间疲劳和凝视诱发性眼球震颤可见于OMG[22]。

MG的鉴别诊断可包括所有核上、核间和核下性传出系统疾病、眼球运动相关的颅神经麻痹(无瞳孔受累)、Lambert Eaton、甲状腺眼肌麻痹、Kearns-Sayre病、慢性和进行性外眼肌麻痹和提上睑肌裂开[14,20]。此外,对复视合并甲状腺相关性眼病的患者中,特别是如果存在外斜视,则应考虑同时合并存在MG[23]。

诊断

MG通常由医生评估症状和进行体格检查开始,并结合实验室、影像学、药理学和生理学测试进行综合诊断[24]。确诊MG需要进行AchR抗体检测,但在OMG 患者中,血液测试的假阴性率高达50%[15]。在80% ~90% 的全身型MG患者体内可检测到循环自身抗体[24]。持续向上注视时的上睑下垂加重是OMG特征性表现[14]。睡眠试验是通过让患者闭上眼睛30分钟,然后在睁眼时立即观察上睑下垂的短暂性改善或消退情况,休息后上睑下垂症状改善可用于MG明确诊断[1]。冰试验可用于区分肌无力性上睑下垂和非肌无力因素导致的上睑下垂。冰试验是一种简单、经济且特异性的方法,具体做法是将冰袋放在上睑下垂患者单侧眼睑上2分钟。上睑下垂改善大于1mm对OMG诊断具有高度敏感性和特异性。有一点需要注意的是,如果患者存在完全的上睑下垂,冰袋试验结果通常是阴性的[20]。氯代膦铵和(或)新斯的明可抑制乙酰胆碱酯酶,给药后出现上睑下垂和(或)眼肌麻痹症状改善,可明确MG的诊断。因这类药物具有心血管副作用,因此,在患有心脏病和正在使用β受体阻滞剂或地高辛的患者中应谨慎考虑使用这些药物。那些具有潜在副作用的侵入性测试正在逐渐被非侵入性的疲劳试验、睡眠试验和冰试验所取代[14]。

近年来,新颖的“强迫眼睑闭合试验”(FECT)已经被发明用于诊断OMG 。这是一个简单的试验,并且具有94%的灵敏度和91%的特异性[25]。在这项筛查试验中,患者被要求紧闭眼睛5~10秒,然后睁开眼睛并保持第一眼位。上眼睑下垂超过原来位置被认为是 FECT阳性[25]。

肌电图和单纤维肌电图是诊断MG最准确的方法,尤其是在血清阴性病例中,因为它们直接测量肌肉对神经受到刺激的电反应。MG患者表现为受刺激神经的复合肌肉动作电位降低[26]。由于OMG患者中全身肌肉受累较少,重复神经刺激具有高特异性和低敏感性[24]。单纤维肌电图比重复刺激神经具有更高的敏感性。据报道,高达99%的MG患者存在单纤维肌电图异常[14]。

尽管有多种检测方法可用于MG,但要明确诊断仍然很困难。由于OMG可以伪装成许多其他原因导致的眼肌麻痹和上睑下垂,对疑似OMG但又不能明确诊断的患者,推荐进行神经影像学检查进行鉴别[14]。

治疗

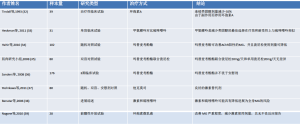

OMG通常由神经内科和眼科共同管理。根据患者就诊时的症状、疾病严重程度和年龄进行个体化治疗[15,27,28]。对于OMG,目前有四种主要的治疗方案:基于症状缓解的短期治疗、长期免疫调节治疗、快速免疫调节治疗和手术治疗[5,29]。大多数临床医生从吡啶斯的明抑制乙酰胆碱酯酶开始。吡啶斯的明的副作用包括:腹泻、腹部绞痛、恶心和呕吐,这些副作用在不同剂量下发生,因此,用药剂量通常是根据治疗的副作用和治疗效果逐渐增加的。MuSK抗体相关的MG患者可能需要更高剂量的吡啶斯的明[5]。在肌无力危象时,可以使用吡啶斯的明静脉给药[30]。低剂量和中等剂量的皮质类固醇通常单独使用或与吡啶斯的明联合使用,以控制免疫反应。长期使用皮质类固醇的副作用,如骨质疏松症、糖尿病、高血压、睡眠障碍和情绪变化,限制了它们在慢性MG管理中的应用[5]。为评估皮质类固醇治疗的风险和安全性而进行的“泼尼松治疗眼肌型重症肌无力的疗效”临床试验表明,低剂量泼尼松治疗对预防OMG进展到全身 MG 是有益的[31]。其他免疫抑制治疗包括硫唑嘌呤、环孢素、霉酚酸酯、他克莫司、甲氨蝶呤、利妥昔单抗和环磷酰胺(表1)。

Full table

除症状缓解外,Wong及其同事报告称,在早期进行免疫抑制剂治疗后,OMG进展为全身型MG的情况减少了30%[40]。

血浆置换、静脉注射免疫球蛋白和血浆置换术可用于对具有致残症状的不稳定和难治性 MG病例进行快速免疫调节。静脉注射免疫球蛋白(IVIGs)包括多克隆免疫球蛋白,可通过 Fab或Fc片段抑制炎症[5]。应按每天0.4 g/kg连续5天或每天1 g/kg连续2天的剂量给药。 IVIG有助于在肌无力危象期间减少机械通气时间。并发症包括过敏反应、体液过多引起的肺水肿、头痛、病毒性肝炎和无菌性脑膜炎[5]。此外,血浆置换具有基于清除循环系统、致病性免疫因子和自身抗体的机制的治疗作用。它可用于难治性病例在进行胸腺切除术和(或)高剂量皮质类固醇冲击治疗前的稳定治疗[41]。

肌无力患者应避免使用以下几种可能加重或诱发MG的药物,包括泰利霉素,一种新的酮内酯抗生素[42];氟喹诺酮类[43,44];链霉素[45];奎尼丁[46] ;羟氯喹[47]和β受体阻滞剂。

MG中的一种新途径治疗可能是Agrin-LRP4-MuSK信号级联。Agrin与LRP4相互作用以激活MuSK酪氨酸激酶受体。MuSK和LRP4准备了复杂的相互作用的蛋白网络,这是 AchR聚集所必需的。Agrin-LRP4-MuSK信号级联驱动AchR并保证神经-肌接头中安全的信号转导[48]。另一项新疗法是依库珠单抗(人源化单克隆抗体)可抑制AchR抗体阳性患者的补体系统。依库珠单抗的用法是35分钟的静脉输注(每个30毫升小瓶含有300毫克依库珠单抗)。它可能是一种对AchR抗体阳性的成人MG或难治性全身型MG患者有价值的新兴疗法[49]。应该做更多的实验以弄清楚该治疗的耐受性、适当的疗程、长期疗效以及并发症。

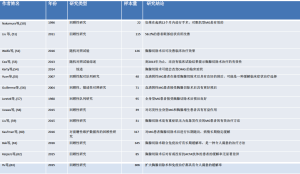

胸腺和胸腺B细胞在MG中抗AchR抗体产生中的作用已有明确报道,因此胸腺切除术可能对治疗有效(表2)[1,11,52,64-66]。术前应获得纵隔影像以排除胸腺瘤。如果存在胸腺瘤,则应进行胸腺切除术,即使没有,在药物不耐受、治疗效果不佳和一线治疗出现严重并发症的情况下也应考虑行胸腺切除术[5,31]。

Full table

虽然OMG的治疗目标是缓解症状,但有时上睑下垂和(或)眼肌麻痹是难治性的。如果上睑下垂相当稳定,则上睑下垂的局部治疗可以包括眼睑支撑架或手术[54,67]。在短期内可以遮盖一只眼睛以治疗复视。如果眼位偏斜相对比较稳定,可以考虑棱镜眼镜。如果眼位非常稳定,可以考虑进行斜视手术[67],虽然斜视手术可能有所帮助,但也有一些并发症包括:复视恶化和暴露性角膜病变的报道[67-69]。

总结

MG可以模仿大多数眼球运动障碍,每个眼科医生都会遇到。眼科医生必须认识到其全身表现并且通常与神经科医生一起协同诊治。由于没有测试能够绝对排除这种情况,诊断可能很困难。因此,眼科医生必须了解以上所描述的各种检测方法,有时也要相信自己的临床判断。MG通常可以被以上所描述的一种或多种方法成功治疗。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Karl C. Golnik and Andrew G. Lee) for the series “Neuro-ophthalmology” published in Annals of Eye Science. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aes.2018.05.02). The series “Neuro-ophthalmology” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. KCG served as unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an Associate Editor-in-Chief of Annals of Eye Science. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Berrih-Aknin S, Frenkian-Cuvelier M, Eymard B. Diagnostic and clinical classification of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun 2014;48-49:143-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peragallo JH, Bitrian E, Kupersmith MJ, et al. Relationship between age, gender, and race in patients presenting with myasthenia gravis with only ocular manifestations. J Neuroophthalmol 2016;36:29-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips WD, Vincent A. Pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis: update on disease types, models, and mechanisms. F1000Res 2016;5. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-1513.

- Verschuuren JJ, Huijbers MG, Plomp JJ, et al. Pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis with antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor, muscle-specific kinase and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:918-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melzer N, Ruck T, Fuhr P, et al. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of myasthenia gravis: a supplement to the Guidelines of the German Neurological Society. J Neurol 2016;263:1473-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pasnoor M, Wolfe GI, Nations S, et al. Clinical findings in MuSK‐antibody positive myasthenia gravis: A US experience. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:370-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, et al. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med 2001;7:365. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nair AG, Patil-Chhablani P, Venkatramani DV, et al. Ocular myasthenia gravis: a review. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014;62:985-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr AS, Cardwell CR, McCarron PO, et al. A systematic review of population based epidemiological studies in Myasthenia Gravis. BMC Neurol 2010;10:46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist K. Familial risks for diseases of myoneural junction and muscle in siblings based on hospitalizations and deaths in sweden. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:573-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Binks S, Vincent A, Palace J. Myasthenia gravis: a clinical-immunological update. J Neurol 2016;263:826-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weizer JS, Lee AG, Coats DK. Myasthenia gravis with ocular involvement in older patients. Can J Ophthalmol 2001;36:26-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCreery KM, Hussein MA, Lee AG, et al. Major review: the clinical spectrum of pediatric myasthenia gravis: blepharoptosis, ophthalmoplegia and strabismus. A report of 14 cases. Binocul Vis Strabismus Q 2002;17:181-6. [PubMed]

- Bhavana Sharma M, Mamatha Pasnoor M, Mazen MDM, et al. Treatment Refractory Ocular Symptoms in Myasthenia Gravis: Clinical and Therapeutic Profile CK Symposium. 2018.

- Gwathmey KG, Burns TM. Myasthenia Gravis. Semin Neurol 2015;35:327-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kupersmith MJ. Ocular myasthenia gravis: treatment successes and failures in patients with long-term follow-up. J Neurol 2009;256:1314-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sussman J, Farrugia ME, Maddison P, et al. Myasthenia gravis: Association of British Neurologists' management guidelines. Pract Neurol 2015;15:199-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Zhang Y, He M. Clinical predictors for the prognosis of myasthenia gravis. BMC Neurol 2017;17:77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evoli A, Alboini PE, Iorio R, et al. Pattern of ocular involvement in myasthenia gravis with MuSK antibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:761-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golnik KC, Pena R, Lee AG, et al. An ice test for the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1282-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee AG. Ocular myasthenia gravis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1996;7:39-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee AG, Brazis PW. Clinical pathways in neuro-ophthalmology: an evidence-based approach. Thieme, 2003.

- Chen CS, Lee AW, Miller NR, et al. Double vision in a patient with thyroid disease: what's the big deal? Surv Ophthalmol 2007;52:434-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okun MS, Charriez CM, Bhatti MT, et al. Tensilon and the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis: are we using the Tensilon test too much? Neurologist 2001;7:295-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Apinyawasisuk S, Zhou X, Tian JJ, et al. Validity of Forced Eyelid Closure Test: A Novel Clinical Screening Test for Ocular Myasthenia Gravis. J Neuroophthalmol 2017;37:253-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Juel VC, Massey JM. Myasthenia gravis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tung CI, Chao D, Al-Zubidi N, et al. Invasive thymoma in ocular myasthenia gravis: diagnostic and prognostic implications. J Neuroophthalmol 2013;33:307-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilhus NE. Myasthenia Gravis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2570-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JI, Jander S. Myasthenia gravis: recent advances in immunopathology and therapy. Expert Rev Neurother 2017;17:287-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skeie GO, Apostolski S, Evoli A, et al. Guidelines for treatment of autoimmune neuromuscular transmission disorders. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:893-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benatar M, McDermott MP, Sanders DB, et al. Efficacy of prednisone for the treatment of ocular myasthenia (EPITOME): A randomized, controlled trial. Muscle Nerve 2016;53:363-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tindall RS, Phillips JT, Rollins JA, et al. A clinical therapeutic trial of cyclosporine in myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993;681:539-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heckmann JM, Rawoot A, Bateman K, et al. A single-blinded trial of methotrexate versus azathioprine as steroid-sparing agents in generalized myasthenia gravis. BMC Neurol 2011;11:97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hehir MK, Burns TM, Alpers J, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in AChR-antibody-positive myasthenia gravis: outcomes in 102 patients. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:593-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muscle Study Group. A trial of mycophenolate mofetil with prednisone as initial immunotherapy in myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2008;71:394-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanders DB, Hart IK, Mantegazza R, et al. An international, phase III, randomized trial of mycophenolate mofetil in myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2008;71:400-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa H, Kiuchi T, Saida T, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tacrolimus in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:970-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benatar M, Kaminski H. Medical and surgical treatment for ocular myasthenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2:CD005081 [PubMed]

- Nagane Y, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, et al. Two-year treatment with cyclosporine microemulsion for responder myasthenia gravis patients. Eur Neurol 2010;64:186-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong SH, Plant GT, Cornblath W. Does treatment of ocular myasthenia gravis with early immunosuppressive therapy prevent secondarily generalization and should it be offered to all such patients? J Neuroophthalmol 2016;36:98-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schroder A, Linker RA, Gold R. Plasmapheresis for neurological disorders. Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9:1331-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perrot X, Bernard N, Vial C, et al. Myasthenia gravis exacerbation or unmasking associated with telithromycin treatment. Neurology 2006;67:2256-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones SC, Sorbello A, Boucher RM. Fluoroquinolone-associated myasthenia gravis exacerbation: evaluation of postmarketing reports from the US FDA adverse event reporting system and a literature review. Drug Saf 2011;34:839-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Gutierrez G, Sereno M, Garcia Vaquero C, et al. Levofloxacin-induced myasthenic crisis. J Emerg Med 2013;45:260-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hokkanen E, Toivakka E. Streptomycin-induced neuromuscular fatigue in myasthenia gravis. Ann Clin Res 1969;1:220-6. [PubMed]

- Stoffer SS, Chandler JH. Quinidine-induced exacerbation of myasthenia gravis in patient with Graves' disease. Arch Intern Med 1980;140:283-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varan O, Kucuk H, Tufan A. Myasthenia gravis due to hydroxychloroquine. Reumatismo 2016;67:125. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohno K, Ohkawara B, Ito M. Agrin-LRP4-MuSK signaling as a therapeutic target for myasthenia gravis and other neuromuscular disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2017;21:949-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dhillon S. Eculizumab: A Review in Generalized Myasthenia Gravis. Drugs 2018;78:367-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura H, Taniguchi Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Delayed remission after thymectomy for myasthenia gravis of the purely ocular type. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;112:371-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Feng H, Yeung SC, et al. Extended transsternal thymectomy for the treatment of ocular myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1993-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolfe GI, Kaminski HJ, Aban IB, et al. Randomized trial of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:511-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cea G, Benatar M, Verdugo RJ, et al. Thymectomy for non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;CD008111 [PubMed]

- Kerty E, Elsais A, Argov Z, et al. EFNS/ENS Guidelines for the treatment of ocular myasthenia. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:687-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan HK, Huang BS, Kung SY, et al. The effectiveness of thymectomy on seronegative generalized myasthenia gravis: comparing with seropositive cases. Acta Neurol Scand 2007;115:181-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guillermo G, Téllez‐Zenteno J, Weder‐Cisneros N, et al. Response of thymectomy: clinical and pathological characteristics among seronegative and seropositive myasthenia gravis patients. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2004;109:217-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaretzki A 3rd, Penn AS, Younger DS, et al. "Maximal" thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1988;95:747-57. [PubMed]

- Uzawa A, Kawaguchi N, Kanai T, et al. Two-year outcome of thymectomy in non-thymomatous late-onset myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 2015;262:1019-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Lai Y, Yao S, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Thymectomy in Myasthenia Gravis Patients with a History of Crisis. World J Surg 2016;40:2681-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaufman AJ, Palatt J, Sivak M, et al. Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: complete stable remission and associated prognostic factors in over 1000 cases. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;28:561-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bak V, Spalek P, Rajcok M, et al. Importance of thymectomy and prognostic factors in the complex treatment of myasthenia gravis. Bratisl Lek Listy 2016;117:195-200. [PubMed]

- Keijzers M, Damoiseaux J, Vigneron A, et al. Do associated auto-antibodies influence the outcome of myasthenia gravis after thymectomy? Autoimmunity 2015;48:552-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu S, Li F, Chen B, et al. Eight-year follow-up of patients with myasthenia gravis after thymectomy. Acta Neurol Scand 2015;131:94-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marx A, Pfister F, Schalke B, et al. The different roles of the thymus in the pathogenesis of the various myasthenia gravis subtypes. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:875-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tiamkao S, Pranboon S, Thepsuthammarat K, et al. Factors predicting the outcomes of elderly hospitalized myasthenia gravis patients: a national database study. Int J Gen Med 2017;10:131-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taioli E, Paschal PK, Liu B, et al. Comparison of Conservative Treatment and Thymectomy on Myasthenia Gravis Outcome. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:1805-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bentley CR, Dawson E, Lee JP. Active management in patients with ocular manifestations of myasthenia gravis. Eye (Lond) 2001;15:18-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morris OC, O'Day J. Strabismus surgery in the management of diplopia caused by myasthenia gravis. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:832. [PubMed]

- Bradley EA, Bartley GB, Chapman KL, et al. Surgical correction of blepharoptosis in patients with myasthenia gravis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;17:103-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

郑文斌

中山大学中山眼科中心。眼科学博士,主治医师,擅长眼科常见病、多发病的诊治。主要从事玻璃体视网膜疾病的基础与临床研究,参与多项科研项目,以第一作者发表SCI论文1篇,中文核心期刊论文1篇。(更新时间:2021/8/12)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Jabbehdari S, Golnik KC. Myasthenia gravis. Ann Eye Sci 2018;3:23.