发展中国家早产儿视网膜病变的临床特点及特征

引言

早产儿视网膜病变(retinopathy of prematurity,ROP)是一种累及早产儿视网膜的增殖性视网膜病变。ROP的范围从轻度自限性疾病到全视网膜脱离和不可逆盲不等。尽管激光光凝治疗是一种非常有效的治疗方法,但是全球仍有超过50000名儿童因ROP[1]而致盲。在西方工业化国家,ROP是潜在可预防儿童盲的主要原因,在印度、拉丁美洲、东欧和中国等发展中国家,ROP是儿童盲的新兴病因[1-3]。

ROP发病率

ROP遍布世界各地;然而,它的发病率在不同的大陆差异很大。据Gilbert等[1]报道,不同地区发病率的差异性可能与该国的婴儿死亡率(infant mortality rates,IMRs)相关。这些指标间接反映了卫生保健设施的质量和可及性以及社会经济发展水平。在撒哈拉以南非洲等婴儿死亡率高(每 1000 例活产儿中有60名以上)的国家,由于早产儿存活率低,ROP的发生率很低。据报道,在发达国家(每 1000 例活产儿的IMR<9)严重ROP的发生率低于20%[4-8]。然而,中低收入国家(每1000名活产儿的IMR 9~60)目前正面临着ROP失明的“流行病”,通常被称为ROP的“第三次流行”。这些国家的新生儿护理设施正在改善,从而提高早产儿的存活率。新生儿支持不足、新生儿护理措施不统一、对ROP缺乏认识、新生儿重症监护室(neonatal intensive care units,NICUs)缺乏ROP筛查程序以及缺乏训练有素的眼科医生来诊断和治疗ROP是发展中国家ROP激增的主要原因。这次ROP的流行和20世纪40—50年代在西方出现的第一次ROP流行有些类似,这要归咎于在出生时滥用氧气治疗呼吸窘迫。

据报道,印度有21.7-51.9%的低出生体重婴儿[9-14]发生ROP。表1比较了印度和其他一些发展中国家关于ROP发病率的各种研究。大多数研究报道平均出生体重超过1250g, 重度ROP的发生率介于5.0%~44.9%之间。据报道, ROP也是一些拉丁美洲国家导致儿童盲的一个重要原因。盲人学校调查[3]显示,在拉丁美洲不同国家接受调查的儿童中,ROP是致盲原因的比例分别为38.6%(古巴)、33.3%(巴拉圭)、17.6%(智利)、14.1%(厄瓜多尔)、10.6%(哥伦比亚)和4.1%(危地马拉)。报道的可治疗ROP发生率从秘鲁利马的19.1%[17]到巴西南部的5.9%[15]不等。

Full table

一些研究强调,与西方相比,中等收入经济体需要更广泛、更具包容性的筛查标准。Jalali等[11]的研究表明,印度有13.3%的婴儿超出了英国和美国的筛查标准。Hungi等[13]在最近的一项研究中报道,57.6%的婴儿比美国的筛查界限中的体重更重,年龄更大。其中36.8%有一定程度的ROP,8%需要治疗。Vinekar等[18]报道,使用美国指南进行筛查时,有17.7%严重ROP的婴儿会被漏诊,使用英国筛查指南进行筛查时,会有22.6%的婴儿会被遗漏。Gilbert等[19]报道,如果遵循英国的筛查标准,一些中低收入国家有13%的婴儿不会进行ROP筛查。这些报道强化了证据,并导致印度ROP筛查标准的修改。自2010年以来,印度一直遵循的筛查指南包括:

- 出生体重﹤1750g的婴儿;和/或

- 胎龄﹤34周的婴儿;

- 较重的婴儿(1750-2000g)或胎龄较大的婴儿(34-36周)可能会进行筛查,这取决于以下危险因素,如机械通气、长期氧疗、血流动力学不稳定或呼吸不畅或心脏疾病状况。

建议在出生后第30天进行ROP的首次筛查检查,而不考虑胎龄。胎龄﹤28周或体重﹤1200g的婴儿应在2-3周时进行早期筛查,以便早期识别急进性后部型ROP(aggressive posterior ROP,APROP)。

目前已达成共识,在政府管理的被称为Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK)国家项目中,对出生体重2000g以下和/或胎龄35周以下的婴儿或临床病程不稳定的高危婴儿(由新生儿医生或儿科专家决定),将ROP作为全面眼科筛查的一部分。

危险因素

早产儿的视网膜在出生时是未完全血管化的。如果出生后的环境与支持视网膜血管和神经发育的子宫内环境不一致,就会发生ROP。其中ROP最一致公认的危险因素是早产的程度。出生体重和胎龄越低,发生ROP的风险越高。这些可能是目前新生儿优质护理地区的主要危险因素,比如工业化西方地区。许多其他的产后因素可能有助于ROP的发生发展。这些危险因素是发展中国家ROP的重要原因,包括额外吸氧[20-22]、脑室内出血[23]、呼吸暂停[24]、机械通气[24]、败血症、表面活性剂治疗[25]、贫血[26]、使用血液制品以及双容量交换输血[27]。

据报道,随着印度未混合氧气的使用,导致较重和更成熟的婴儿出现APROP[28]。在这些眼睛中进行的荧光素血管造影显示大量毛细血管退化,类似于缺氧致ROP实验动物模型中所见的血管闭塞[29]。出生后6周体重增长率低(即体重增长低于出生体重的50%)被认为是ROP的独立危险因素,也是严重ROP的预测指标[30]。

未成熟的视网膜不仅易受高于子宫内氧水平的影响,而且易受氧张力的变化和缺乏通常在子宫内提供的营养和生长因子的影响,从而导致血管停止生长。新生儿医生和护士可以通过在NICU实施基于证据和成本效益的措施以减少一些危险因素,如严格遵守预先设定的氧饱和度目标、实施无菌操作、手卫生常规、鼓励母乳喂养、袋鼠式护理和限制性输血政策。

临床特征

ROP的临床特征包括视网膜有血管区与无血管区之间的分界线,嵴样隆起,从视网膜表面向玻璃体生长的视网膜外纤维血管增生,牵拉性视网膜脱离,全视网膜脱离,白斑,镰状皱襞、视网膜及玻璃体出血。一般来说,ROP经过五期(Ⅰ-Ⅴ),国际ROP分类(International Classification of ROP,ICROP)[31]对其进行了明确定义,并被普遍遵循。根据视网膜病变的部位,ROP被划分为三个分区。ROP通常是阶段性或逐步进展,直至达到治疗期或发生全视网膜脱离,导致不可逆盲。

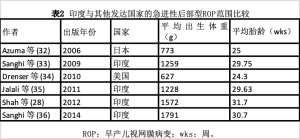

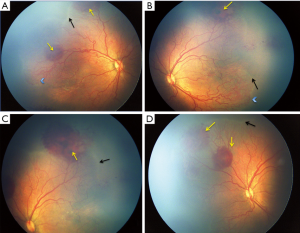

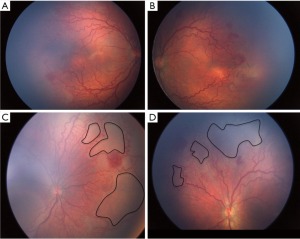

最近的ICROP分类[31]描述了一种更严重、更急进性的ROP,称为APROP,它有不经过中间期而直接进展到第Ⅴ期的倾向。尤其是发展中国家正面临着APROP的激增,因此在早期处理此类潜在致盲病例的上面临着挑战。表2比较了印度和其他工业化国家的各种研究报道的APROP范围。在西方,这种形式的ROP发生在极低出生体重和胎龄极低的婴儿[32,34]。与此相反,在发展中国家,APROP发生在更高出生体重(图1)和胎龄[28,33,35,36]的婴儿。这种形式的APROP可能进展迅速,导致早于“出生的第30天”即出生后2-3周进行筛查的指征形成。据报道,较重婴儿的APROP[36]最常发生在后极部II区,与I区APROP中发育较差的血管相比,后极部视网膜血管更为成熟。此外,血管向鼻侧视网膜延伸相当长的距离,形成包围视网膜无血管区的大环(图2)。

Full table

印度报道了一种非典型性的APROP,称为“混合型ROP”(图1),根据目前的ICROP分类标准很难进行分类,因为它既有APROP的特征,也有在进展期ROP见到的嵴样隆起或者血管化后部视网膜中的垫状视网膜前增殖形成[36]。

ROP治疗可使用二极管激光器或532nm绿激光器进行,无论哪种激光具有同等疗效均可[37]。早产儿视网膜病变的早期治疗(Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity,ETROP)研究[38]推荐如下,即 I 区的任何期病变伴 Plus 病变 ;I区的 3 期病变不伴 Plus病变;2 区的 2 期或 3 期病变伴 Plus 病变。除了ETROP研究指南外,APROP有必要在48-72小时内进行早期治疗。

发展中国家ROP筛查的挑战

如前所述,ROP的表现和严重程度因不同地理区域的婴儿致盲ROP的“风险”而有所不同。例如,印度遵循的筛查指南已被修改,以使覆盖范围最大化,将严重ROP的漏诊机会降至最小。尽管在大多数情况下及时的诊断和治疗就可以提供良好的视觉效果,但发展中国家今天面临的最大挑战实际上是缺乏及时的筛查。大多数2级和3级NICUs没有ROP筛查程序,因此没有进行ROP筛查。这与高度可变的用氧标准和其他新生儿护理措施有关。由于缺乏预见性,ROP筛查滞后于NICUs和特殊新生儿监护室(Special Newborn Care Units,SNCUs)的激增,这些可能成为未来致盲的潜在温床。规划和执行机构、新生儿护理团队缺乏意识以及缺乏训练有素和感兴趣的眼科医生是造成这种情况的原因。目前ROP发病率较低的国家(如撒哈拉以南非洲)应借鉴中等收入发展中国家的经验,制定包括严格的ROP筛查方案在内的新生儿护理扩展计划。对任何一个ROP专家来说,看到一个双眼Ⅴ期ROP的婴儿是最可怕的噩梦,然而他们中的大多数人几乎每周都要见到来自新地理区域的越来越多的Ⅴ期ROP婴儿。在这个时期,要说服和劝说家人已经失去了治疗机会,视力预后很差,这是极其困难的。这些已经导致ROP相关盲病例中的法医诉讼发生率日益增加。在印度一家三级保健转诊中心[39]的一份报告中,86.4%的Ⅴ期ROP患儿从未接受过ROP筛查。近74.2%是父母发现孩子看不见东西时带来的(即自荐)。儿科医生没有对任何婴儿进行筛查,25.8%的婴儿是由眼科医生推荐。在发展中国家的一个示范性项目[40]KIDROP中,由训练有素的技术人员使用RetCam进行宽视野视网膜成像被证明是非常有效的。与ROP专家相比,这种使用训练有素的技术人员记录疾病以及治疗和转诊决策的模式具有95.7%的敏感性、93.2%的特异性和81.5%的阳性预测值。在没有训练有素的眼科医生的情况下,这可能是一条出路。

结论

新生儿医生、眼科医生、护理工作者、父母以及政府之间的密切合作是解决ROP致盲这一新问题的必要条件。在监管所有早产儿/高危新生儿的设施中, 有必要执行严格的ROP筛查服务的法律。需要关注的是,通过改善新生儿护理进行一级预防,通过病例发现和治疗进行二级预防。这些应该包括提供必要的设备和接受过ROP检查培训的人员以及适当的转诊服务。其最终目的是降低ROP的发生率和严重程度,以最佳方式发现和治疗病例,使这些早产儿享有看得见的机会。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Rajvardhan Azad, Peiquan Zhao and Helen Mintz-Hittner) for the series “Retinopathy of Prematurity” published in Annals of Eye Science. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aes.2017.12.08). The series “Retinopathy of Prematurity” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gilbert C. Retinopathy of prematurity: a global perspective of the epidemics, population of babies at risk and implications for control. Early Hum Dev 2008;84:77-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kong L, Fry M, Al-Samarraie M, et al. An update on progress and the changing epidemiology of causes of childhood blindness worldwide. J AAPOS 2012;16:501-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilbert C, Rahi J, Eckstein M, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in middle-income countries. Lancet 1997;350:12-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Painter SL, Wilkinson AR, Desai P, et al. Incidence and treatment of retinopathy in England between 1990 and 2011: database study. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:807-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V, et al. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics 2005;116:15-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmer EA, Flynn JT, Hardy RJ, et al. Incidence and early course of retinopathy of prematurity. The Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1628-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed MA, Duncan M, Kent A, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment in infants born greater than 30 weeks’ gestation and with a birth weight greater than 1250 g from 1998 to 2002: a regional study. J Paediatr Child Health 2006;42:337-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Austeng D, Kallen KB, Ewald UW, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in infants born before 27 weeks’ gestation in Sweden. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:1315-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charan R, Dogra MR, Gupta A, et al. The incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in a neonatal care unit. Indian J Ophthalmol 1995;43:123-6. [PubMed]

- Gopal L, Sharma T, Ramchandran S. Retinopathy of prematurity: a study. Indian J Ophthalmol 1995;43:59-61. [PubMed]

- Jalali S, Matalia J, Hussain A, et al. Modification of screening criteria for retinopathy of prematurity in India and other middle-income countries. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:966-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari S, Patwardhan V, Vaidya U, Kadam S, Kamat A. Retinopathy of prematurity in a tertiary care center—incidence, risk factors and outcome. Indian Pediatr 2009;46:219-24. [PubMed]

- Hungi B, Vinekar A, Datti N, et al. Retinopathy of Prematurity in a rural neonatal intensive care unit in South India-a prospective study. Indian J Pediatr 2012;79:911-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varughese S, Jain S, Gupta N, et al. Magnitude of the problem of retinopathy of prematurity. Experience in a large maternity unit with a medium size level-3 nursery. Indian J Ophthalmol 2001;49:187-8. [PubMed]

- Fortes Filho JB, Eckert GU, Valiatti FB, et al. Prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity: an institutional cross-sectional study of preterm infants in Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2009;26:216-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Zhou X, Zhang Q, Ji X, Zhang Q, Zhu J, Chen C, Zhao P. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity in China: a neonatal units-based prospective study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:8229-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turkowsky JD, Cervantes AC, Rocha PV, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and its evolution in the population preterms of very low birth weight survivors and that was discharged from the Instituto Especializado Materno Perinatal of Lima. Rev Peru Pediatr 2007;60:88-92.

- Vinekar A, Dogra MR, Sangtam T, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in Asian Indian babies weighing greater than 1250 grams at birth: Ten year data from a tertiary care center in a developing country. Indian J Ophthalmol 2007;55:331-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilbert C, Fielder A, Gordillo L, et al. Characteristics of infants with severe retinopathy of prematurity in countries with low, moderate, and high levels of development: implications for screening programs. Pediatrics 2005;115:e518-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stenson B, Brocklehurst P, Tarnow-Mordi W. Increased 36-week survival with high oxygen saturation target in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1680-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- . Supplemental Therapeutic Oxygen for Prethreshold Retinopathy Of Prematurity (STOP-ROP), a randomized, controlled trial. I: primary outcomes. Pediatrics 2000;105:295-310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen ML, Guo L, Smith LE, et al. High or low oxygen saturation and severe retinopathy of prematurity: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2010;125:e1483-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim TI, Sohn J, Pi SY. Postnatal risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2004;18:130-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah VA, Yeo CL, Ling YL. Incidence, risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity among very low birth weight infants in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:169-78. [PubMed]

- Karna P, Muttineni J, Angell L. Retinopathy of prematurity and risk factors: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2005;5:18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Englert JA, Saunders RA, Purohit D. The effect of anemia on retinopathy of prematurity in extremely low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 2001;21:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dutta S, Narang S, Narang A, et al. Risk factors of threshold retinopathy of prematurity. Indian Pediatr 2004;41:665-71. [PubMed]

- Shah PK, Narendran V, Kalpana N. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity in large preterm babies in South India. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012;97:F371-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, et al. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994;35:101-11. [PubMed]

- Fortes Filho JB, Bonomo PP, Maia M, et al. Weight gain measured at 6 weeks after birth as a predictor for severe retinopathy of prematurity: study with 317 very low birth weight preterm babies. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009;247:831-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:991-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Azuma N, Ishikawa K, Hama Y, et al. Early vitreous surgery for aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:636-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Das P, et al. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity in Asian Indian babies: Spectrum of disease and outcome after laser treatment. Retina 2009;29:1335-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drenser KA, Trese MT, Capone A. Aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Retina 2010;30:S37-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jalali S, Kesarwani S, Hussain A. Outcomes of a protocol-based management for zone 1retinopathy of prematurity: The Indian Twin Cities ROP screening program report number. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:719-24.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Dogra M, et al. A hybrid form of retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:519-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Vinekar A, et al. Frequency-doubled Nd:YAG (532 nm green) versus diode laser (810 nm) in treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:1264-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:1684-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanghi G, Dogra MR, Katoch D, et al. Demographic profile of infants with stage 5 retinopathy of prematurity in North India: implications for screening. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2011;18:72-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vinekar A, Gilbert C, Dogra M, et al. The KIDROP model of combining strategies for providing retinopathy of prematurity screening in underserved areas in India using wide-field imaging, tele-medicine, non-physician graders and smart phone reporting. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014;62:41-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

宋新志

甘肃省人民医院。眼科医学硕士,毕业于郑州大学,甘肃省人民医院眼科医生。主要从事白内障、青光眼及眼底病(眼底外科方向)的临床研究,近五年以第一作者发表中文核心期刊论文1篇,目前2篇SCI论文正在外审中。(更新时间:2021/8/12)

李淑婷

常州市第一人民医院。毕业上海交通大学,眼科学医学博士,主治医师,江苏省“双创博士”人才培养对象,常州市的高层次人才引进对象。常州市医学会内分泌分会糖尿病眼病学组委员,主持江苏省自然基金青年项目和常州市应用基础研究计划项目各一项,参与国家自然基金面上项目一项,共发表论文共20余篇,以第一作者/通讯作者发表论文11篇。(更新时间:2021/7/28)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Dogra MR, Katoch D. Clinical features and characteristics of retinopathy of prematurity in developing countries. Ann Eye Sci 2018;3:4.