The good doctor: more than medical knowledge & surgical skill

Introduction

You have worked hard in school over many years to excel in academic and extracurricular activities. You submitted a strong application for successful entry into medical school during which time you doubled up on your academic productivity and soaked in everything that you could possibly learn about medicine. You feel that your academic productivity paid off since you were able to obtain a residency in your favorite field: ophthalmology. You are excited about becoming the best ophthalmic physician and surgeon that you can be. You already know what it takes to tackle large amounts of medical information and you have a feeling that you have the proper kinesthetic skills to become a competent surgeon. So how come this is not enough to be a good doctor?

There is no doubt that mastery of medical knowledge and surgical skill is absolutely essential for practicing ophthalmology. Yet this is insufficient to be a good doctor.

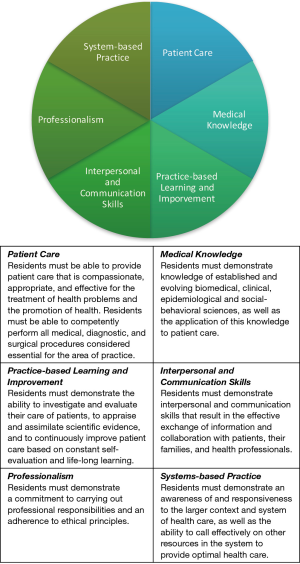

We all have our own personal concept of what it means to be a good doctor, but our own understanding is only the beginning of a journey of discovery, refinement and continual awareness of your ability to provide effective and compassionate care that patients expect you to deliver. The trouble is that each patient has their own perspective of the type of care that they envision receiving. Therefore, a physician is not able to deliver care in a singular way and be considered a good doctor. Being a good doctor does not happen overnight. It is a very serious commitment to yourself, your family and the patients that you serve. It is presumed that industriousness, cognitive knowledge, and excellent motor skills are prerequisites. So, what are some attributes that make a physician and surgeon a “good doctor?” Well, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has described six core clinical competencies that are required for a physician to be competent to practice medicine independently and without supervision (1), In fact, in order to relate to your patient properly and to treat them to your best ability, it is essential during your training to strive perform equally well in all six of the following competencies: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, system-based practice (Figure 1).

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Core Clinical Competencies

Patient care

Residents must be able to provide patient care that is compassionate, appropriate, and effective for the treatment of health problems and the promotion of health. Residents must be able to competently perform all medical, diagnostic, and surgical procedures considered essential for the area of practice.

Medical knowledge

Residents must demonstrate knowledge of established and evolving biomedical, clinical, epidemiological and social-behavioral sciences, as well as the application of this knowledge to patient care.

Practice-based learning and improvement

Residents must demonstrate the ability to investigate and evaluate their care of patients, to appraise and assimilate scientific evidence, and to continuously improve patient care based on constant self-evaluation and life-long learning. Residents are expected to develop skills and habits to be able to meet the following goals: (I) identify strengths, deficiencies, and limits in one’s knowledge and expertise; (II) set learning and improvement goals; (III) identify and perform appropriate learning activities; (IV) systematically analyze practice using quality improvement methods, and implement changes with the goal of practice improvement; (V) incorporate formative evaluation feedback into daily practice; (VI) locate, appraise, and assimilate evidence from scientific studies related to their patients’ health problems; (VII) use information technology to optimize learning; and, participate in the education of patients, families, students, residents and other health professionals.

Interpersonal and communication skills

Residents must demonstrate interpersonal and communication skills that result in the effective exchange of information and collaboration with patients, their families, and health professionals. Residents are expected to: (I) communicate effectively with patients, families, and the public, as appropriate, across a broad range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds; (II) communicate effectively with physicians, other health professionals, and health related agencies; (III) work effectively as a member or leader of a health care team or other professional group; (IV) act in a consultative role to other physicians and health professionals; and, (V) maintain comprehensive, timely, and legible medical records.

Professionalism

Residents must demonstrate a commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles. Residents are expected to demonstrate: (I) compassion, integrity, and respect for others; (II) responsiveness to patient needs that supersedes self-interest; (III) respect for patient privacy and autonomy; (IV) accountability to patients, society and the profession; and, sensitivity and responsiveness to a diverse patient population, including but not limited to diversity in gender, age, culture, race, religion, disabilities, and sexual orientation.

Systems-based practice

Residents must demonstrate an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context and system of health care, as well as the ability to call effectively on other resources in the system to provide optimal health care. Residents are expected to: (I) work effectively in various health care delivery settings and systems relevant to their clinical specialty; (II) coordinate patient care within the health care system relevant to their clinical specialty; (III) incorporate considerations of cost awareness and risk benefit analysis in patient and/or population-based care as appropriate; (IV) advocate for quality patient care and optimal patient care systems; (V) work in inter-professional teams to enhance patient safety and improve patient care quality; and, (VI) participate in identifying system errors and implementing potential systems solutions.

Ok, this information is helpful, but what are some personal behaviors that can help you fulfill these competencies? Here are some attributes that will help you to fulfill all six ACGME core clinical competencies during your medical training and will remain essential throughout a good doctor’s career (Table 1): (2-9).

Table 1

| Professionalism |

| Open-mindedness |

| Compassion |

| Attentiveness |

| Self-improvement |

| Empathy |

| Calmness |

| Adaptability |

| Passion |

| Confidence and humility |

Professionalism

Medicine is unequivocally a field where professionalism is fundamental. Professionalism imbues the relationship between medicine and society. Professionalism is the basis of patient-physician trust. Professionalism in medicine attempts to illustrate the attitudes, behaviors, and characteristics that are desired in the medical profession.

What are some aspects expected of professionalism in medicine? Being a physician means having a contract with society where there are certain expectations. These expectations include the assurance that the physician is competent in acting as a healer or provider of health. Society expects good doctors to behave with morality, integrity, objectivity and accountability. By nature, the field is altruistic and provides service to society. Further, society expects good doctors to not only promote the well-being of individual patients but also be experts and advocate for the public good through teaching, research or community service.

What is an example of acting with integrity? A key aspect of physician behavior is maintaining patient-physician confidentiality. Patients need to feel safe that personal information, whether verbalized or digitally or physically stored, is kept secure and only privy to those involved in the patient’s care. Patients need to feel assured that they are treated with privacy and dignity. If you are inclined to reveal patient information or gossip to individuals not involved in the patient’s care, you are breaking the trust between you and the patient.

Open-mindedness

A good doctor must be able to treat all patients regardless of their ethnicity, culture, religion, gender, age, lifestyle choices, or conduct. The job is to treat the patient and not to judge them. Open-mindedness is an active process. Preconceptions that creep into our minds when seeing patients with lives different from our own are important to be aware of but need to be kept in check so as to treat the issue at hand as the patient is placing their trust in you. The next examination room that you walk into may be a leader in the community or a person without a permanent home. It is essential to strive to give each patient the same care and attention that you would expect from your doctor.

Empathy

When a physician attempts to understand how a person feels at the beginning of the encounter, an empathetic connection is made straight away. An attempt to understand how a person feels and how their condition is affecting their quality of life or their activities of daily living is key in understanding whether and how the physician might be able to help that patient. When a patient experiences the physician’s attempt to understand their situation, a therapeutic relationship is built. The patient feels that they are being cared for and that the physician has taken an interest in their well-being. There is an investment by the physician in the form of time and patience when listening actively to the patient’s concerns and trying to understand how this fits in their life. Such a therapeutic relationship is more likely to result in suitable, personalized solutions for the patient and is key to an effective bedside manner.

Are you able to understand or get along with people from different walks of life? If so, you are likely to not only exhibit open-mindedness but also empathy. These are important attributes since a high degree of stress is generated when a patient perceives that the doctor does not show interest in how a medical condition makes a person feel.

Compassion

The good doctor understands that as humans we are all susceptible to the same vulnerabilities, fears, temptations, and frustrations as anyone else. Good doctors must have a heart that is as big and strong as their mind. Efficient delivery of health care or mechanical completion of amazingly elegant surgical maneuvers are important skills for a physician to have, but are inadequate for the patient to regard the doctor as being good. Just as the surgeon needs to learn, understand and hone surgical skills, the good doctor needs to continue to learn about human nature and to practice and refine their interpersonal and communication skills. By developing these skills, the good doctor is prepared to practice medicine and master the essentials of patient care.

Calmness

When activities become busy in the clinic or hospital, the atmosphere becomes hectic. If competing factors overly conflict, what was hectic can become chaotic. Conflict and chaos are not therapeutic. In treating the human body, the practice of medicine is not always pleasant. Unfamiliar and unexpected developments may occur and at times these instances are stressful or perhaps even a bit gruesome. This is more likely the case during surgery or during urgent, emergent, or intensive care. Patients look to the health care team to keep steady temperaments during these times. Good doctors are physicians and surgeons who are able to cope and deal with these situations with composure and calmness. Doing so allows the health care team to make the correct decisions swiftly and reassures the patient and family that they are cared for.

Attentiveness

A good doctor will make eye contact with the patient when greeting them by name. A good doctor will face the patient and ask how they are feeling. A good doctor will try to allow the patient to describe why they are in and what they hope to accomplish during the visit. If this is a returning patient, a good doctor will remember something about the last visit and continue to build rapport with the patient. The patient may have indicated in their previous visit that they were going to see their grandchild graduate from school and during a return visit a good doctor would ask about that experience. A good doctor would be vigilant to ensure that medical conditions or medication side effects are not complicating patient complaints. During an encounter when there are numerous complaints, a good doctor will identify the key issue and try to address the primary or most modifiable issue in order to make most of the patient’s appointment. A good doctor is able to sit down and listen to the patient even when the clinic is busy. A good doctor communicates with the care team involved in the patient’s care. A good doctor provides referrals and resources for instances when it is clear that the patient requires help beyond the scope of the physician’s ability.

Adaptability

Medical technologies and discoveries are continually changing the landscape of medicine and the delivery of care. The health care environment demands that physicians remain cognizant and adaptable to new developments in order to provide the most effective care. There are times when the clinic or hospital must adjust to external factors in order to maintain proper patient care. Factors such as emergencies, inclement weather, office staff leave, malfunctioning equipment, or hospital or healthcare policies episodically disrupt the delivery of care. Sometimes these disruptions lead to improvement in care, but at other times, the storm needs to be weathered while maintaining proper patient care.

Self-improvement

Medicine changes all the time. Surgical techniques and equipment change all the time. The good doctor works to keep up to date with new findings, innovative research, and emerging theories at all times. Learning continues the moment when a physician graduates from training. The good doctor strives toward perfection, but all the while understands that they will never attain it. These days, physicians are required to demonstrate that they are involved in projects actively looking at improving the delivery of patient care. These activities may be related to medical research, patient safety initiatives, and practice management projects. Even after the day that you have graduated, you should never stop learning. Continuing medical education, professional development, board certification, teaching, journal clubs, scientific meetings, and on-line tutorials are mechanisms by which good doctors engage in self-improvement.

Passion

Passion and enthusiasm, when forthright, is infectious. Patients recognize this straight away as one of the attributes of good doctors. Patients are able to feel whether physicians love their work. If you love the practice of medicine and surgery with its perils and pitfalls, you hold an important puzzle piece of being a good doctor. Patients are drawn to those dedicated to improving the lives of others and spending long hours in teaching, healing, or medical discovery. Although this puzzle piece may be easy to hold, it is deceivingly easy to lose. Good doctors have such high levels of industry and altruism, yet at the end of the day, physicians and surgeons are humans just like our patients. Good doctors need to understand that they are equally as vulnerable to discomfort and disease as their patients. Through strong work ethic and the ability to delay gratification, physicians can lose passion in their work and burnout. Doctors must be careful to recognize the propensity for burnout and prevent it. It is essential for physicians to be able to have time to sleep, eat, play and recreate in a healthful way. A healthy balance can fuel love and passion.

Confidence and humility

These attributes are listed together since the good doctor’s confidence is checked by humility. Joining these attributes is essential to prevent confidence from transitioning to arrogance and/or complacency. Patients and other members of the health care team are more inclined to entrust their care to a physician who exhibits confidence in their capability through their demeanor, words and deeds. A successful physician may possess tremendous knowledge base through study and may exercise decisive clinical judgment learned through experience, but when the confident physician is lulled to inattentiveness, they may find themselves arrogant and/or complacent. Medicine is an ever-changing field and patient conditions may manifest themselves in unique ways. Both arrogance and complacency erode the trust in the therapeutic relationship between a patient and physician. The good doctor possesses a healthy dose of confidence and an equally healthy dose of humility. A good doctor is a lifelong learner and is familiar with numerous clinical presentations and a wealth of medical knowledge but is also open-minded to the new.

The importance of being an advocate for your patient to ensure that effective communication occurs between the physician and patient cannot be overstated. It has been shown that poor communication within the health care team and especially poor doctor patient communication results in a higher likelihood of malpractice claims (10-13).

Conclusions

In addition to strong medical knowledge and outstanding surgical skills, developing these attributes is essential to becoming a good doctor. In those moments when you will feel that you are a good doctor, there will be a corresponding circumstance that will teach you something to improve upon. Welcome to this journey; one of the most noble of endeavors.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Unrestricted Grant Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York, USA and Casey NIH Core grant (P30 EY010572), Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Karl C. Golnik, Dan Liang and Danying Zheng) for the series “Medical Education for Ophthalmology Training” published in Annals of Eye Science. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aes.2017.05.04). The series “Medical Education for Ophthalmology Training” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements pages 9-12. Available online: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_07012016.pdf. Last accessed April 24,2017.

- Sims T, Tsai JL, Koopmann-Holm B, et al. Choosing a physician depends on how you want to feel: the role of ideal affect in health-related decision making. Emotion 2014;14:187-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- . Seven characteristics of the ideal physician. Health News 2006;12:12. [PubMed]

- Gochman DS, Stukenborg GJ, Feler A. The ideal physician: implications for contemporary hospital marketing. J Health Care Mark 1986;6:17-25. [PubMed]

- Fones CS, Kua EH, Goh LG. 'What makes a good doctor?'--views of the medical profession and the public in setting priorities for medical education. Singapore Med J 1998;39:537-42. [PubMed]

- Kelly AM, Mullan PB, Gruppen LD. The Evolution of Professionalism in Medicine and Radiology. Acad Radiol 2016;23:531-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hillis DJ, Grigg MJ. Professionalism and the role of medical colleges. Surgeon 2015;13:292-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education, Board on Global Health, Institute of Medicine. Establishing Transdisciplinary Professionalism for Improving Health Outcomes: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2014 Apr 7.

- Wynia MK, Papadakis MA, Sullivan WM, et al. More than a list of values and desired behaviors: a foundational understanding of medical professionalism. Acad Med 2014;89:712-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levinson W, Hudak P, Tricco AC. A systematic review of surgeon-patient communication: strengths and opportunities for improvement. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:3-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lussier MT, Richard C. Doctor-patient communication: complaints and legal actions. Can Fam Physician 2005;51:37-9. [PubMed]

- Virshup BB, Oppenberg AA, Coleman MM. Strategic risk management: reducing malpractice claims through more effective patient-doctor communication. Am J Med Qual 1999;14:153-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beckman H. Communication and malpractice: why patients sue their physicians. Cleve Clin J Med 1995;62:84-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Lauer AK, Lauer DA. The good doctor: more than medical knowledge & surgical skill. Ann Eye Sci 2017;2:36.